Background

The greatest challenge in cancer treatment is eradicating cancer cells with minimal loss of normal cells. To address this challenge, targeted therapies have been developed, significantly improving the therapeutic index compared to traditional chemotherapy and radiotherapy cancer treatments. Antibodies are an important member of the targeted therapy family of drugs due to their exceptionally high specificity for their target antigens. Therapeutic antibodies, antibody-drug conjugates, and immune checkpoint antibodies have been developed, while bispecific antibodies have been synthesized and designed to redirect a patient's T cells to kill cancer cells.

May 13, 2024, American researchers published an article titled "Cancer therapy with antibodies" in Nature Reviews Cancer. The article summarizes the different methods used by therapeutic antibodies to target cancer cells, discusses their mechanisms of action, the structural basis of targeting specificity, clinical applications, and ongoing research to improve efficacy and reduce toxicity.

Antibody development

Traditionally, monoclonal antibodies have been produced using hybridoma technology, developed by Cesar Milstein and Georges Kohler in 1975. This hybridoma technology generated a series of mouse monoclonal antibodies, which were stable and cost-effective. However, the injection of mouse antibodies into humans resulted in the production of human anti-mouse antibodies (HAMA) that limited their efficacy and increased adverse reactions. The subsequent advent of chimeric antibodies failed to address this issue. To further reduce unwanted immune responses, a process called humanization, developed in the 1980s, was used to increase the human content of mouse monoclonal antibodies. Humanization involves grafting only the complementarity-determining regions (CDRs) of a mouse antibody onto the framework regions of a human antibody. In addition to mouse hybridoma technology, rabbit hybridoma technology has also been developed for the production of rabbit monoclonal antibodies targeting tumor antigens. CDR grafting has been used to humanize rabbit monoclonal antibodies, such as YP218 targeting mesothelin, for clinical development. Fully human antibodies were generated with the help of two technologies developed in the 1990s: human antibody phage display technology and the expression of human antibodies in transgenic mouse models. In addition, the latest single B cell antibody development technology further optimizes antibody diversity and high-throughput accessibility.

The antibodies currently entering clinical trials are either humanized or fully humanized antibodies. According to previous experimental results, humanized antibodies and fully humanized antibodies generally have similar effects in patients.

Different forms of antibodies

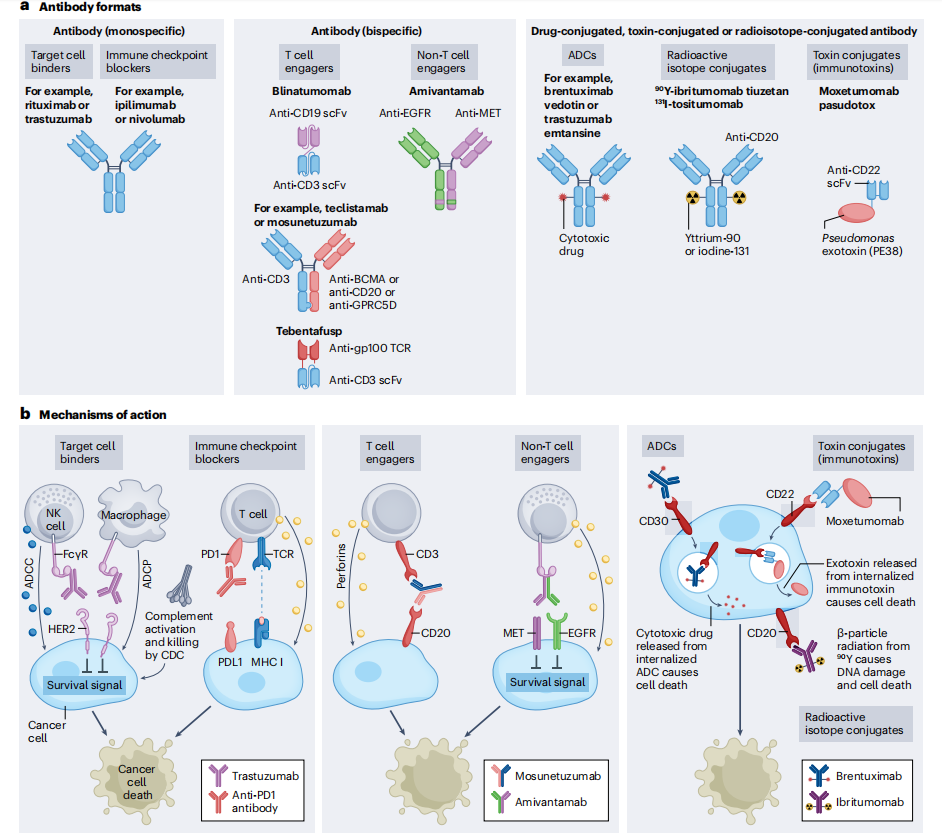

Antibody therapies can be divided into three main forms based on their structure and functional mechanisms: monospecific antibodies, bispecific antibodies, and antibodies conjugated to payloads (such as drugs, toxins, and radiopharmaceuticals). These different types and mechanisms of antibody use offer a variety of strategies to target and kill cancer cells, each with its own unique advantages and potential applications, bringing new hope to cancer treatment.

Monospecific antibodies

Monospecific antibodies are full-length immunoglobulins that bind to a target antigen. They have five subtypes: IgG, IgM, IgA, IgE, and IgD. Only IgG4 binds to the neonatal Fc receptor (FcRn), resulting in a long half-life of approximately 21 days. Most FDA- and EMA-approved antibodies, as well as those under development, use the IgG antibody format. IgG antibodies have four subclasses (IgG1, IgG2, IgG3, and IgG4), with most therapeutic antibodies utilizing the IgG1 subclass. Monospecific antibodies generally target cell surface proteins, primarily growth factor receptors that are overexpressed in solid cancers. For hematological malignancies, antibodies are typically directed against cell surface glycoproteins (also known as cluster of differentiation (CD) markers) expressed by different immune cell subsets.

Monospecific antibodies bind to antigens on cancer cells, leading to cell death through multiple mechanisms, including disruption of survival signals through growth factor receptors such as human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), activation of immune cells such as natural killer (NK) cell-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and macrophage-mediated antibody-dependent cellular phagocytosis (ADCP), and activation of the complement cascade (complement-dependent cytotoxicity (CDC)). Immune checkpoint blockade antibodies bind to and activate immune cells such as T cells, leading to immune-mediated cancer cell death.

Human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2)-specific antibodies bind to distinct HER2 epitopes. The structure of the HER2 extracellular domain (ECD) bound to the fragment antigen-binding (Fab) domains of trastuzumab and pertuzumab guided the design of the bispecific antibody zanidatamab. This structural analysis technique was used to understand the therapeutic mechanism of rituximab. Structural analysis revealed that CD20 forms a dimer, with each CD20 molecule bound to a single rituximab Fab. Rituximab promotes CD20 aggregation by cross-linking CD20 dimers to form a large supramolecular complex.

Monospecific antibody Fc engineering: Most IgG1 antibody effector functions are mediated by the Fc domain. Common Fc domain modifications include focusing (removing the focus from the Fc region to increase FcγrIIIa binding) or amino acid substitutions of key residues (such as S239D and I332E to increase binding to Fc receptors). Both modifications lead to enhanced ADCC and ADCP.

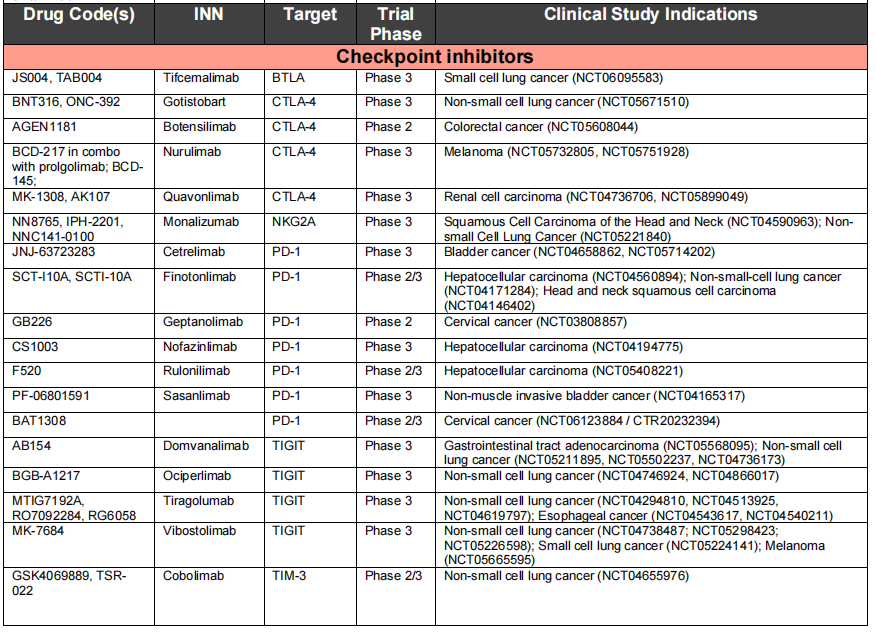

Immune checkpoint inhibitors: Monospecific antibodies targeting immune cell regulatory checkpoints have shown significant clinical efficacy in cancer patients. Eleven immune checkpoint inhibitory antibodies approved by the FDA and EMA are currently being used to treat more than 20 different types of cancer, including lung cancer, melanoma, renal cell carcinoma, and head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, and several more of these inhibitory antibodies are expected to be approved in the near future.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors inhibit negative regulatory T cells by blocking antibodies, thereby reactivating cytotoxic T cells and killing cancer cells. Three proteins or pathways targeted by therapeutic antibodies approved by the FDA or EMA are CTLA4, PD1-PDL1, and LAG3. PD1-blocking antibodies are currently the most widely used immune checkpoint inhibitors. The seven approved PD1-blocking antibodies and two currently in clinical trials use the IgG4 format, which, compared to the IgG1 isotype, does not effectively activate the complement cascade and has weaker Fc receptor binding. Therefore, the IgG4 format may protect PD1-expressing effector T cells from inadvertent killing by ADCC or CDC. All IgG4 antibodies carry the S228P mutation to prevent Fab arm exchange. Biological analysis revealed that the two PD1-blocking antibodies, pembrolizumab and nivolumab, bind to different epitopes on PD1 that overlap with the ligand PDL1 binding site, thereby preventing PD1-PDL1 interaction. The crystal structure of a PDL1-targeting antibody in complex with PDL1 and PDL2 identified a key residue (Trp100) in PDL2 that hinders the binding of anti-PDL1 antibodies to PDL2 and provides a mechanism of selectivity between PDL1 and PDL2.

Two CTLA4-targeting antibodies, I pilimumab and T remeli-mumab, have similar binding epitopes and can effectively compete with the natural ligands CD80 and CD86.

Immune checkpoint blockade antibodies mediate cancer cell killing through general immune activation, which can sometimes be misdirected toward healthy tissue. Immune checkpoint inhibitory antibodies are associated with a highly pronounced spectrum of adverse reactions, known as immune-related adverse events (IRAEs). Severe and potentially fatal toxicities can occasionally occur. In many cases, temporary immunosuppression with glucocorticoids, tumor necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists, mycophenolate mofetil, or other immunomodulators is required to manage IRAs.

Bispecific antibodies

Bispecific antibodies can bind to two different antigens or epitopes. The antigens can be located on the same target cell or on different target cells. Most bispecific antibodies targeting two different cell types are T cell engagers, cross-linking cancer cells with effector cells. These are called T cell engager (TCE) bispecific antibodies. After cross-linking, the effector T cells are activated and kill the bound target cancer cells by releasing cytotoxic granules and lymphokines. Another type of bispecific antibody binds to different antigens expressed by the same target cell, such as two different growth factor receptors. These bispecific antibodies kill the target cells by blocking proliferation signals through the target growth factor receptors and activating NK cells and macrophages to kill cancer cells.

Common TCE bispecific antibody formats include BiTE, Genmab, DART, and Xmab, among which Blinatumomab uses the BiTE format. Glofitamab is a CD20xCD3 bispecific antibody for lymphoma and has a unique 2:1 T cell engagement bispecific format, which has a higher tumor killing effect compared to the traditional 1:1 target cell and CD3 binding design. The format generally used for full-length therapeutic antibodies is IgG type. IgG has two antigen binding sites, and IgM is a pentamer with 10 antigen binding sites, which provides higher binding affinity compared to IgG antibodies targeting the same epitope. Imvotamab is a CD20xCD3 IgM bispecific antibody that has shown complete remission in patients with advanced B-cell malignancies.

Blinatumomab consists of the minimal elements required for a bispecific antibody: a cancer-targeting scFv (anti-CD19). Blinatumomab targets B cells through the anti-CD19 scFv , while the anti-CD3 scFv simultaneously engages and activates T cells, leading to B cell death. Blinatumomab has demonstrated activity across a range of B-cell malignancies and is approved for the treatment of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B- ALL).

Bispecific antibodies are also designed to bind to two different antigens or epitopes on target cancer cells without involving effector T cells. Their anti-cancer effects are mediated by blocking two proliferative signaling pathways, thereby maximizing anti-tumor activity. In addition to their receptor-blocking activity, these bispecific antibodies can also be engineered to contain a functional IgG1 Fc domain, enabling them to kill cancer cells through non-T cell immune effector pathways such as ADCC, ADCP, and CDC. Amivantamab is the first receptor-blocking bispecific antibody to target both EGFR and MET expressed on cancer cells and is approved for the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer. Amivantamab's IgG1 Fc domain is designed to have low binding levels, thereby enhancing FcγR IIIa binding and NK cell-mediated ADCC. TCE bispecific antibodies can cause cytokine release syndrome (CRS) and neurotoxicity, while receptor-blocking bispecific antibodies cannot activate T cells and generally do not induce CRS and neurotoxicity.

Conjugated Antibodies

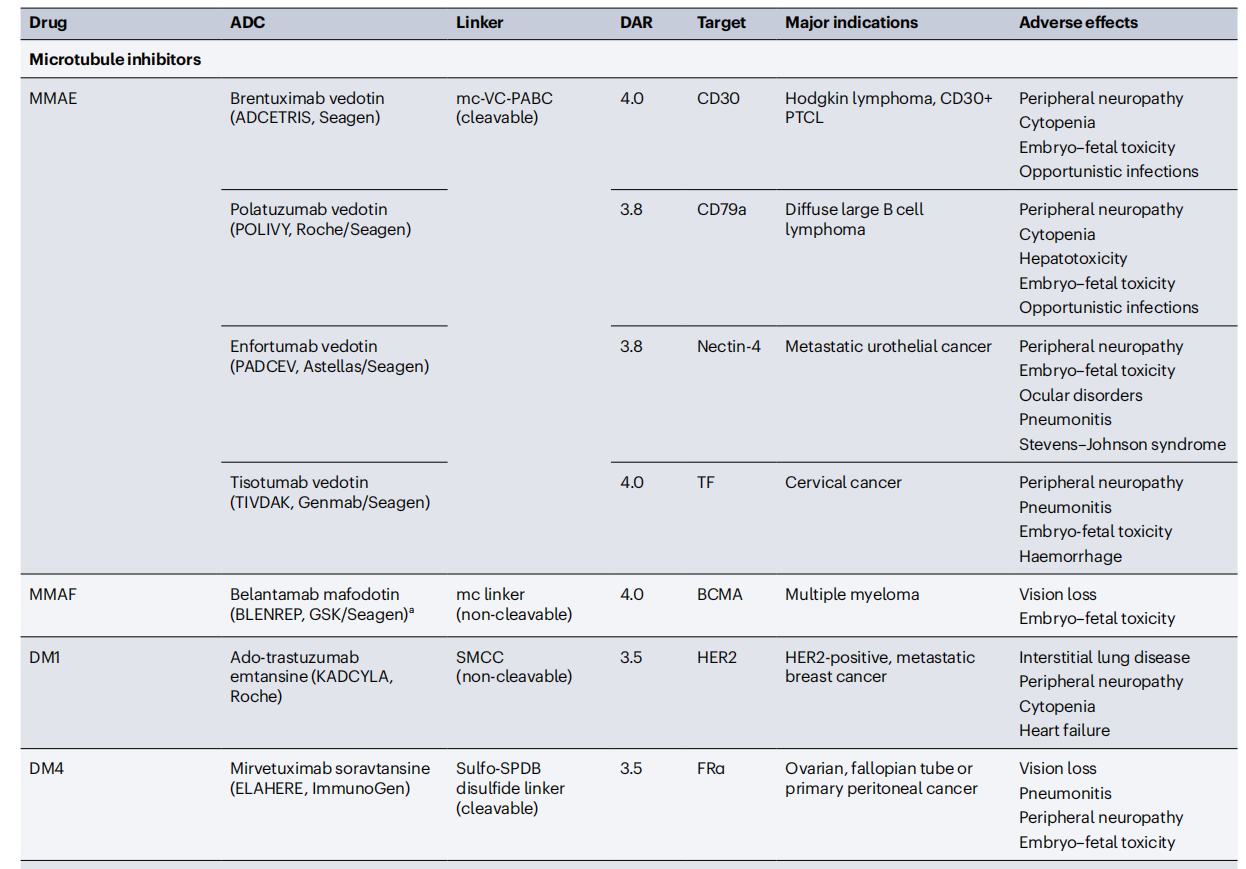

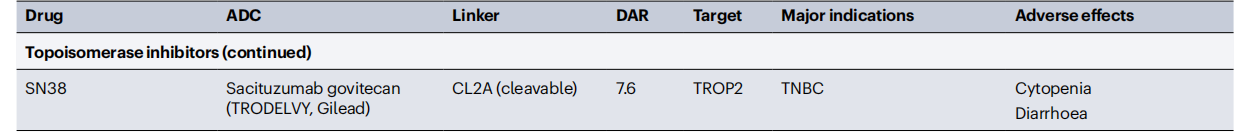

Conjugated antibodies include antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs), immunotoxins, and antibodies linked to radioactive isotopes, which enhance the antibody's ability to kill cells. ADCs are constructed by linking tumor-targeting antibodies to cytotoxic drugs. ADC molecules bind to cell surface antigens, leading to their internalization and subsequent release of the cytotoxic drug within the cell. This allows for the selective delivery of cytotoxic drugs to cancer cells while sparing most healthy tissue. The key components of an ADC include a tumor-targeting antibody, a cytotoxic drug, and a linker that connects the antibody to the cytotoxic drug. Some ADC drugs have demonstrated significant clinical success, selectively delivering potent cytotoxic drugs to cancer cells.

Challenges and Future Outlook

Oncology drug development is an arduous process, with a success rate of 3%. Specifically in the oncology field, data on the success rate of antibody-based therapies is currently lacking, with approximately 18% of therapeutic antibodies entering Phase I trials and then reaching market approval. These low figures reflect the many obstacles encountered during drug development. Compared to hematological malignancies, antibody development for solid tumors lags, primarily due to a lack of targetable antigens. Different lymphoma subtypes account for approximately 3% of all cancer deaths, and five tumor antigens (CD19, CD20, CD79b, CD30, CCR4, and PD1) are targeted by therapeutic antibodies. In contrast, lung cancer, which accounts for approximately 21% of cancer deaths, has only one targetable tumor antigen (EGFR-MET).

The method to circumvent the lack of tumor-specific antigens can be targeted through a combination of multiple antigens. Secondly, targeting a combination of antigens that are co-expressed only in tumors and not in healthy tissues may provide a viable therapeutic approach. The academic community is currently looking for targeting tumor-specific antigens, intracellular antigens, and antigens in the tumor microenvironment. Targeting low-density antigens remains a challenge, and researchers are exploring the use of optimized antibody engineering to address this limitation, thereby effectively targeting new antigens and other low-abundance targets.

An antibody targeting the p53 (R175H) peptide bound to the major histocompatibility complex (MHC) binds parallel to the peptide, in contrast to the specific T cell receptor (TCR), which binds perpendicularly to the peptide. Furthermore, the antibody's affinity for the p53 (R175H) neoantigen is approximately 100-fold higher than that of the corresponding TCR. This distinct binding mechanism likely contributes to the antibody's specificity and high affinity, providing a foundation for the development of new therapeutic antibodies.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors play an important role in targeted therapy. The FDA and EMA have approved 11 different versions of CTLA4, PD1, and PDL1-targeting antibodies for 65 different indications across more than 20 types of cancer. However, current immune checkpoint inhibitors can cause complications, approximately 1% of which are fatal and 40% have chronic toxicities. Prioritizing basic and translational research on new immune checkpoint modulators, such as B cell and T lymphocyte attenuators (BTLAs), is crucial.

To improve efficacy and overcome some of the limitations of antibodies, new antibody formats and engineering strategies are under continuous development. For example, novel bispecific formats, trispecific antibodies, and alpaca antibodies with enhanced affinity are being developed. Antibodies can selectively target cancer cells by exploiting the low pH, active proteases, and specific antigens found in the tumor microenvironment, allowing them to gain or lose function when environmental conditions change. Antibody therapies also utilize antibodies with masking mechanisms. By improving the linker, payload, and targeting moiety, novel conjugated antibodies are being designed to target cancer cells. We need to select the appropriate antibody format for each target.