The complement system consists of a series of plasma protein interactions that directly attack pathogens and trigger inflammation. Most complement proteins are zymogens that, when activated by cleavage, become proteases. All three complement pathways—the classical pathway (CP), the lectin pathway (LP), and the alternative pathway (AP)—produce C3 convertase, which is present on the pathogen surface. The C3 convertase complex cleaves C3 into C3a and C3b. C3b is a membrane-associated protein that covalently binds to other complement proteins already present on the pathogen surface. Following C3b binding, the complement protein complex on the cell surface forms C5 convertase. In the classical pathway, C5 convertase consists of C4b2a3b, while in the alternative pathway, it is C3bBbC3b. Both C5 convertases perform the same function: cleaving C5 into its two active components, C5a and C5b, which play important roles in subsequent immune pathways.

(Data source: Goran B , et al. EMBO J. 2015)

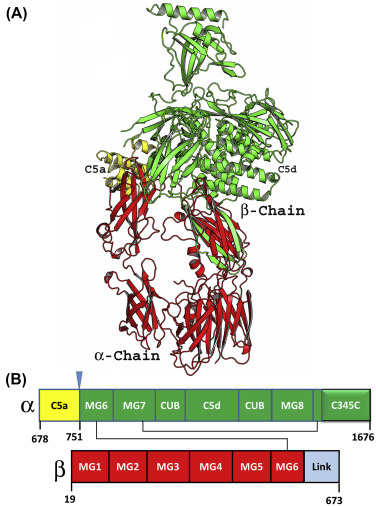

C5 composition

The C5 molecule has a molecular weight of approximately 190 kDa and consists of two chains (α, 115 kDa and β, 75 kDa) linked by a disulfide bond. C5 convertase proteolytically cleaves C5 75 residues downstream of the N-terminus of the C5 α chain, releasing an inflammatory fragment, C5a, and the activated form, C5b.

(Data source: The Complement Facts Book)

C5a

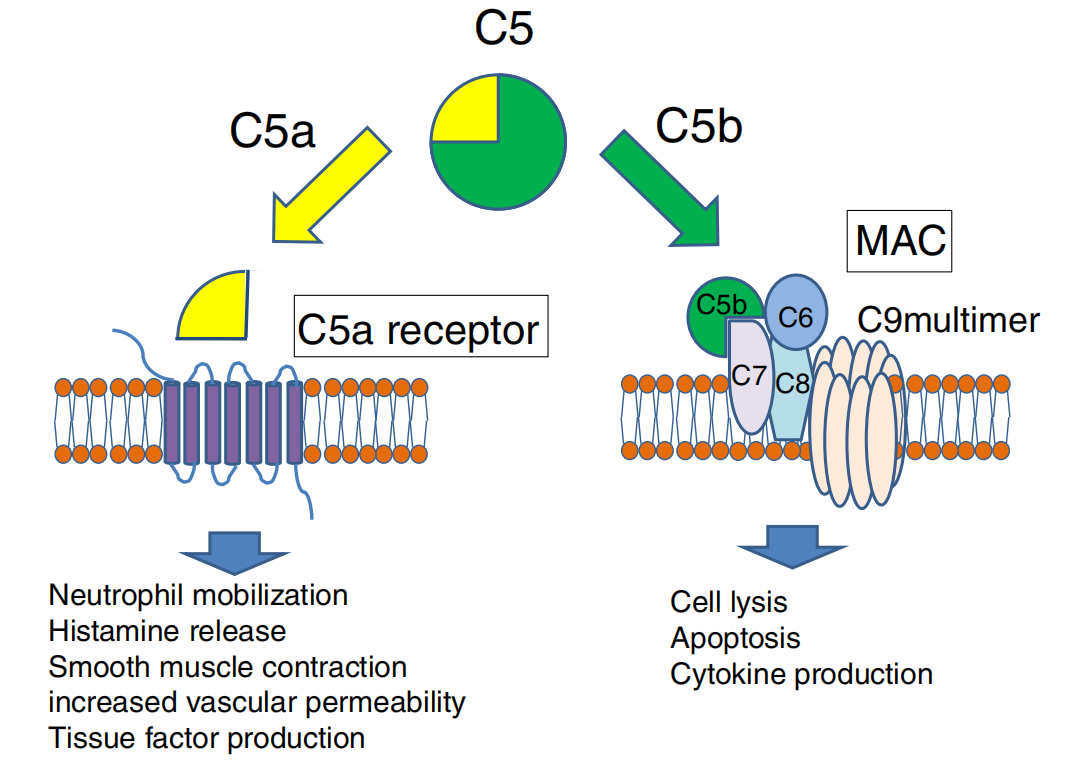

The smaller fragment produced by C5 cleavage is C5a (77-74 amino acids in length), a potent inflammatory molecule. C5a has three core disulfide bonds and a disordered C-terminus. Like the coiled-coil structure of other tetrahelical proteins, the first 63 residues of C5a in solution form an antiparallel bundle of four helices. The N-terminal helix is amphipathic. C5a is highly conserved across most organisms, including most cytokines, but human C5a exhibits some molecular differences. Furthermore, the C-terminus is heavily glycosylated.

(Data source: Kohidai, L. 2008)

C5b

The C5b protein consists of an α chain (104 kDa) and a β chain (75 kDa). After cleavage, C5b interacts nonenzymatically with other complement proteins to form the MAC. The C5b fragment initially exposes a high-affinity binding site for C6 and C7. The binding domains of C5b for other complement proteins, such as C6 and C7, have recently been characterized and are homologous to the complement binding domains on C3 and C4.

(Data source: Alexander E , et al. J Biol Chem. 2012)

Overall, complement component C5 plays a key role in the complement system, connecting innate immune defense and inflammatory responses. Its cleavage into C5a and C5b drives two key pathways: inflammatory signaling and the formation of the membrane attack complex (MAC).

(Data source: Takahiko H , et al. Inflamm Regen. 2016)

C5-mediated diseases

The dual functions of C5 (C5a enhances the inflammatory response, while C5b forms MAC to directly kill foreign substances) puts it in a key position as a potential target.

Septicemia

Serious bloodstream infections caused by Gram-negative bacteria can trigger the release of systemic anaphylatoxins, namely C5a and C3a, which can lead to septic shock and hypotension. The danger of systemic complement activation in sepsis lies in the powerful inflammatory response triggered by activated complement. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) is characterized by the global release of activated anaphylatoxins, which can lead to septic shock and death.

Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE)

A visceral autoimmune disease, defined as an immune response directed against the host and involving the complement system. Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) is more likely to occur in individuals with low complement levels. The complement deficiency associated with SLE is due to genetic mutations at specific complement loci, possibly near the C5 (chromosome 9q33) locus. These mutations result in excessive inflammation (C5a, C3a, C4a) and cytolysis (MAC, C5b).

Liver fibrosis

Scarring of liver tissue is often associated with severe liver disease. The link between C5 and liver fibrosis remains unclear, but one study suggests a possible causal role for the C5 gene. Using a mouse model, inhibition of the C5a receptor in hepatocytes from individuals infected with hepatitis C demonstrated an antifibrotic effect in vivo. Because the C5 gene is conserved in many organisms, this relationship between C5a and liver fibrosis may also hold true in humans (Hillebrandt et al., 2005).

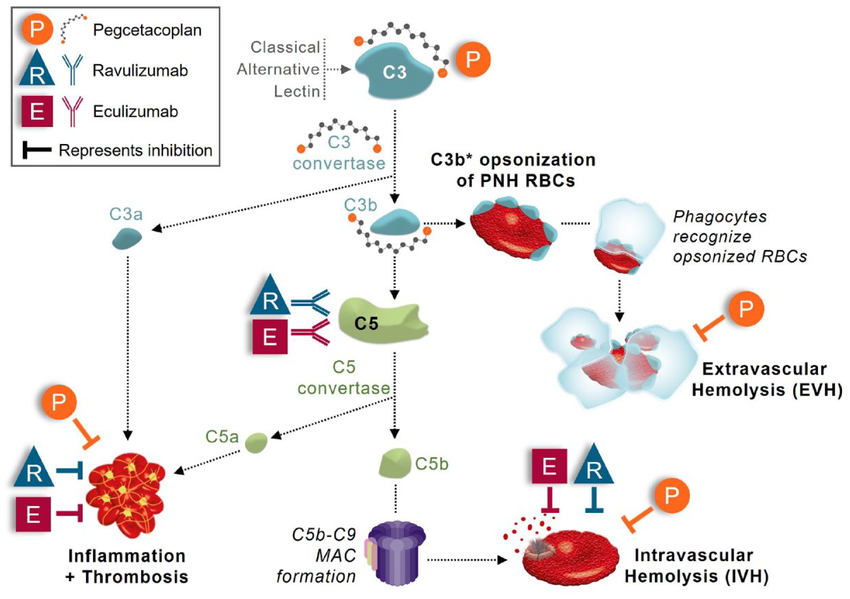

Targeted therapy for C5

Targeting C3 and C5 were the earliest candidate targets for treatment of the complement system. Anti-C5 antibodies became the second complement-targeted drug and the first complement inhibitor to enter the clinic: Eculizumab, a humanized anti-C5 monoclonal antibody developed by Alexion, was administered by intravenous infusion and approved by the FDA in 2007 for the treatment of hemoglobinuria PNH.

The significant success of Alexion's C5 antibody has increased attempts to control uncontrolled C5 activity, such as crovalimab, an anti-C5 antibody for subcutaneous administration (Roche).

Ravulizumab represents the next generation of engineered eculizumab-derived antibodies. Ravulizumab differs from eculizumab at four amino acids and has improved pharmacokinetics due to increased recycling of the antibody at the neonatal Fc receptor, resulting in prolonged plasma circulation and reduced dosing frequency.

(Data source: Raymond S, et al. Ther Adv Hematol. 2022)

Currently, anti-C5 therapy is the most successful and widely used complement-targeted drug and the standard treatment for paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria (PNH) and hereditary von Willebrand disease (aHUS).