Protein-protein interactions (PPIs) play a crucial role in biological function, participating in cellular biological processes such as cell cycle regulation and signal transduction. Traditional methods for analyzing PPIs include co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP), GST, and pull-down assays. However, these assays are performed in vitro and cannot truly reflect the interactions between proteins within cells. The newly developed proximity labeling (PL) technique can be performed directly within living cells under natural conditions, facilitating the capture of transient or weak protein interactions in vivo. It plays a role in protein-protein interactions and has important applications in the spatial dynamics of the transcriptome and proteome, histone modifications, subcellular localization, and drug target discovery. Proximity labeling (PL) combined with mass spectrometry (MS)-based quantitative proteomics has become a powerful approach for characterizing PPIs.

Proximity labeling technology principle

Proximity labeling (PL) uses engineered enzymes, such as peroxidases or biotin ligases, to genetically tag a protein of interest (POI). PL enzymes convert inert small molecule substrates into short-lived reactive species that diffuse away from the enzyme's active site and covalently label nearby endogenous species. The substrate molecule typically contains a biotin handle, allowing subsequent enrichment of the labeled species using streptavidin beads and identification by mass spectrometry (for proteins) or nucleic acid sequencing (for RNA).

(Data source: Qin W, et al. Nat Methods. 2021.)

Types and development of proximity labeling methods

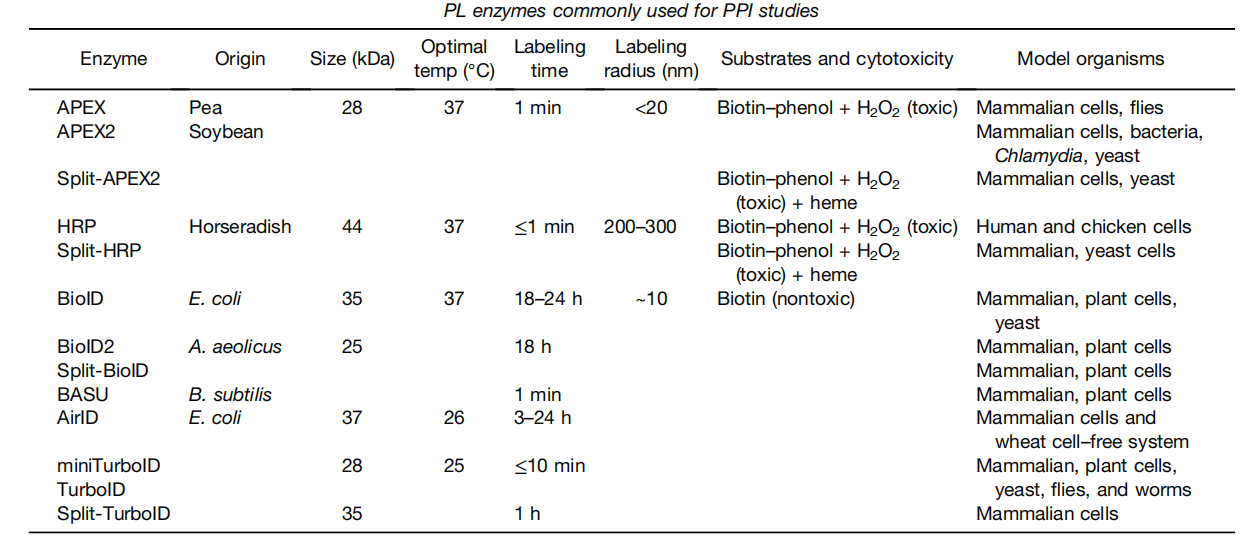

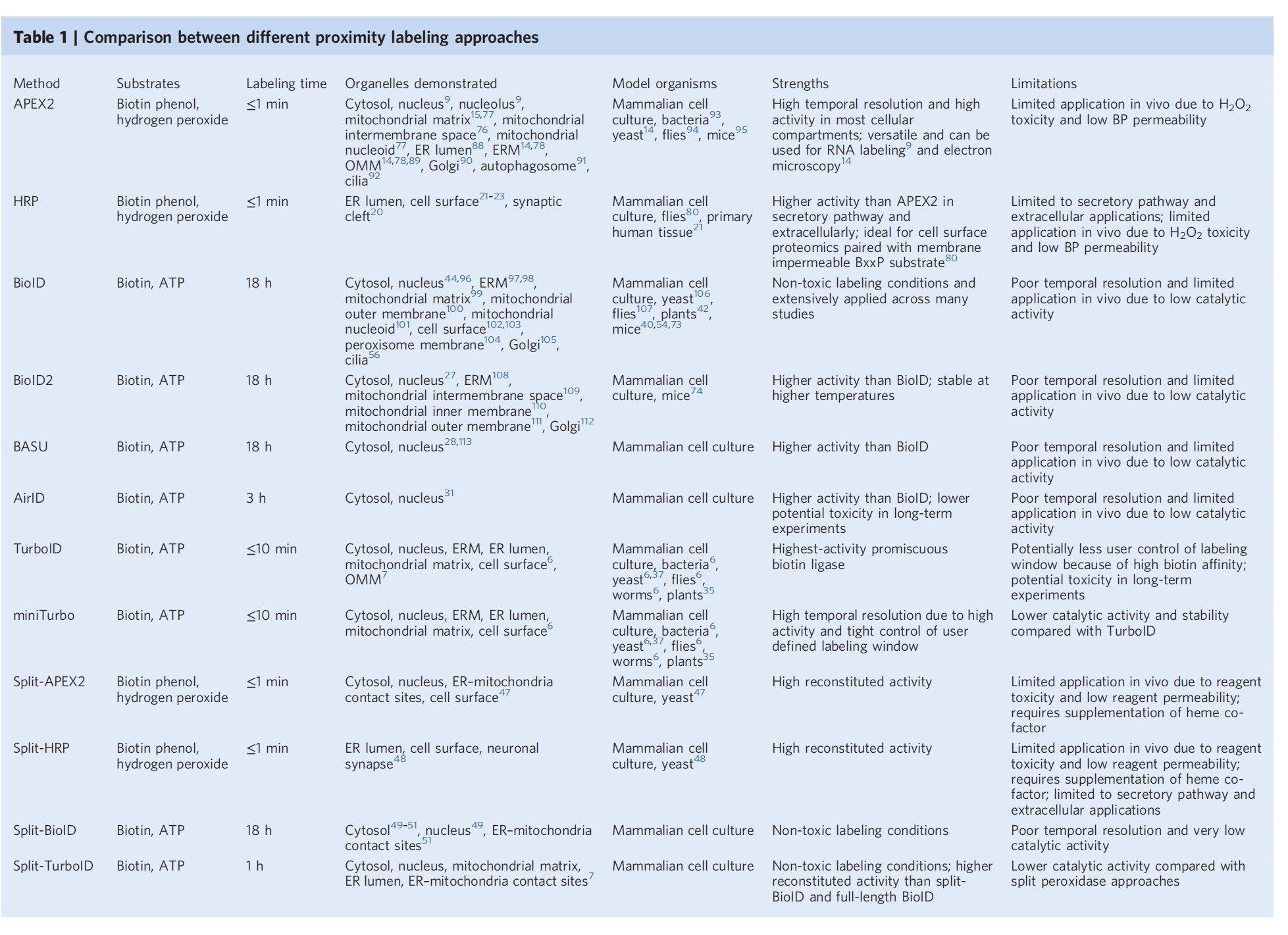

There are two main types of proximity labeling methods, peroxidase labeling (such as APEX , APEX2, Split-APEX2) and biotin labeling (such as BioID, TurboID, miniTurbo, Split-TurboID).

(Data source: Mathew B, et al. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2022.)

Biotin ligase-based proximity labeling

BiolD series of proximity markers

BiolD: A variant of the Escherichia coli biotin ligase BirA with a molecular weight of 35 kDa, BioID can covalently label lysine residues on proteins within a 10 nm radius. However, the large molecular weight of BioID hinders its targeting in certain fusion proteins and requires a long labeling time.

BioID2: In 2016, Kim et al. developed a smaller enzyme, BioID2 , with a molecular weight of 27 kDa, derived from Aquifex aeolicus. Compared to BioID, BioID2 has higher selectivity for targeting fusion proteins, requires less supplemental biotin, and exhibits enhanced labeling of neighboring proteins. BioID2 not only improves the efficiency of protein-protein interaction screening but also allows for specific regulation of the biotin labeling radius.

TurboID Series Proximity Markers

TurboID: In 2018, a new PL enzyme, TurboID (35 kDa), was developed based on the directed evolution of BirA displayed in yeast. TurboID has 15 mutated base pairs, enabling it to use ATP to convert biotin to biotin-AMP, a reactive intermediate that subsequently covalently labels nearby proteins. It is the most biologically active biotin ligase, capable of utilizing endogenous biotin in certain cells and organisms, exhibiting biotinylation activity prior to the addition of exogenous biotin. Due to its evolution through the yeast secretory pathway, TurboID exhibits significantly higher activity in the endoplasmic reticulum lumen than BioID.

miniTurbo: Also developed based on yeast-displayed BirA, miniTurbo has a molecular weight of only 28 kDa. It contains an N-terminal domain deletion and a 13 bp mutation. This further reduces potential interference with fusion protein trafficking and function. miniTurbo's low affinity for biotin precludes labeling in the absence of high exogenous biotin concentrations, allowing for tighter control of the labeling time window.

Peroxidase-based proximity labeling

HRP: Horseradish peroxidase (HRP) is the first proximity labeling enzyme capable of converting aryl azide-biotin reagents into free radicals. It is active only in the secretory pathway, such as within endoplasmic reticulum tubules and on the cell surface. This method facilitates the study of the protein composition of cell membrane domains. Furthermore, when combined with mass spectrometry, it allows for the investigation of molecular interactions at the cell surface.

APEX: APEX is a novel proximity labeling enzyme derived from dimeric pea or soybean ascorbate peroxidase by Martell et al. in 2012. APEX lacks disulfide bonds and calcium-binding sites, has a small molecular weight (approximately 28 kDa), and functions as a monomer. APEX targets intracellular organelles or specific protein complexes. After only 1 minute of treatment of live cells with biotin-phenol in H₂O₂ , APEX catalyzes the one-electron oxidation of biotin-phenol to form biotin-phenoxyl radicals. This radical can react with interacting tyrosine residues within the labeling radius or with tyrosine residues on neighboring proteins to form covalent adducts. Although these radicals are extremely short-lived, they covalently label endogenous proteins in the vicinity of APEX. Recently, this technology has played a crucial role in determining the protein composition of the human mitochondrial matrix and intermembrane space (IMS) proteome and the topology of the mitochondrial calcium uniporter.

(Data source: Mathew B, et al. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2022)

APEX2: APEX2 is a variant of APEX generated through directed evolution using a yeast display platform and fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) screening. Compared to APEX, it exhibits improved thermal stability and higher biotinylation activity. APEX2 is also more sensitive when used in electron microscopy, allowing staining across a large field of view without the need for specialized equipment. This method can replace indirect measurement techniques (such as subcellular fractionation) and can be used for protease accessibility testing or western blotting to precisely determine the subcellular localization and membrane topology of important proteins.

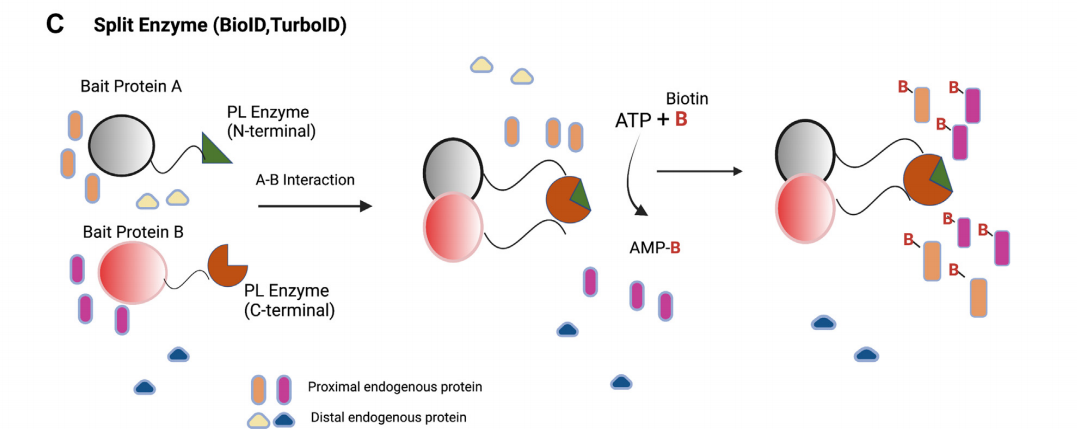

Proximity labeling based on Split-PL

The Split-PL system can be used to study spatiotemporally defined binary protein complexes and other interacting components at membrane contact sites. PL enzymes (such as HRP, APEX2, BioID, or TurboID) are split into two poorly interacting, non-functional fragments that can reassemble to restore activity when fused to two interacting proteins.

(Data source: Mathew B, et al. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2022)

Split-BioID: Split-BioID has a molecular weight of 35 kDa. It enables the verification of protein-protein interactions and the simultaneous labeling of other adjacent proteins belonging to the corresponding complex in living cells, thus overcoming the limitations of affinity purification and BioID methods. The split-BioID system effectively reduces background biotinylation.

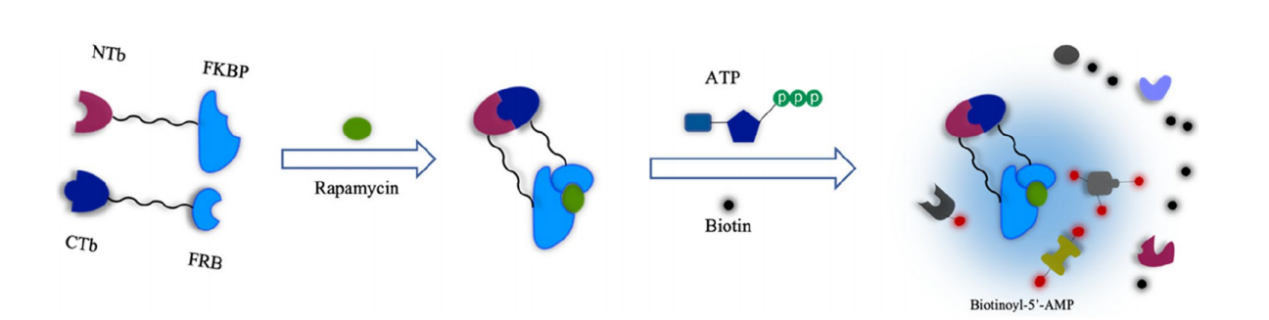

Split-TurboID: Split-TurboID has a molecular weight of 35 kDa. When Split-TurboID is applied to the FRB-FKBP dimer system and treated with rapamycin, the two inactive fragments of TurboID reassemble to form an active enzyme that produces biotin-5'-AMP. Split-TurboID is available in low-affinity and high-affinity forms. Both methods catalyze proximity labeling in less than 1 hour of biotin incubation, with activity significantly higher than not only split-BioID but also full-length BioID.

(Data source: Guo J, et al. Cell Commun Signal. 2023)

Split-APEX2: The plit-APEX2 method. This enzyme consists of two parts: AP and EX. AP is a 200-amino acid N-terminal fragment selected from a yeast display library, and EX is a 50-amino acid C-terminal fragment. Split-APEX2 technology has been applied to mammalian cell membranes, noncoding RNA scaffolds, and mitochondria-associated endoplasmic reticulum contact sites.

(Data source: Guo J, et al. Cell Commun Signal. 2023)

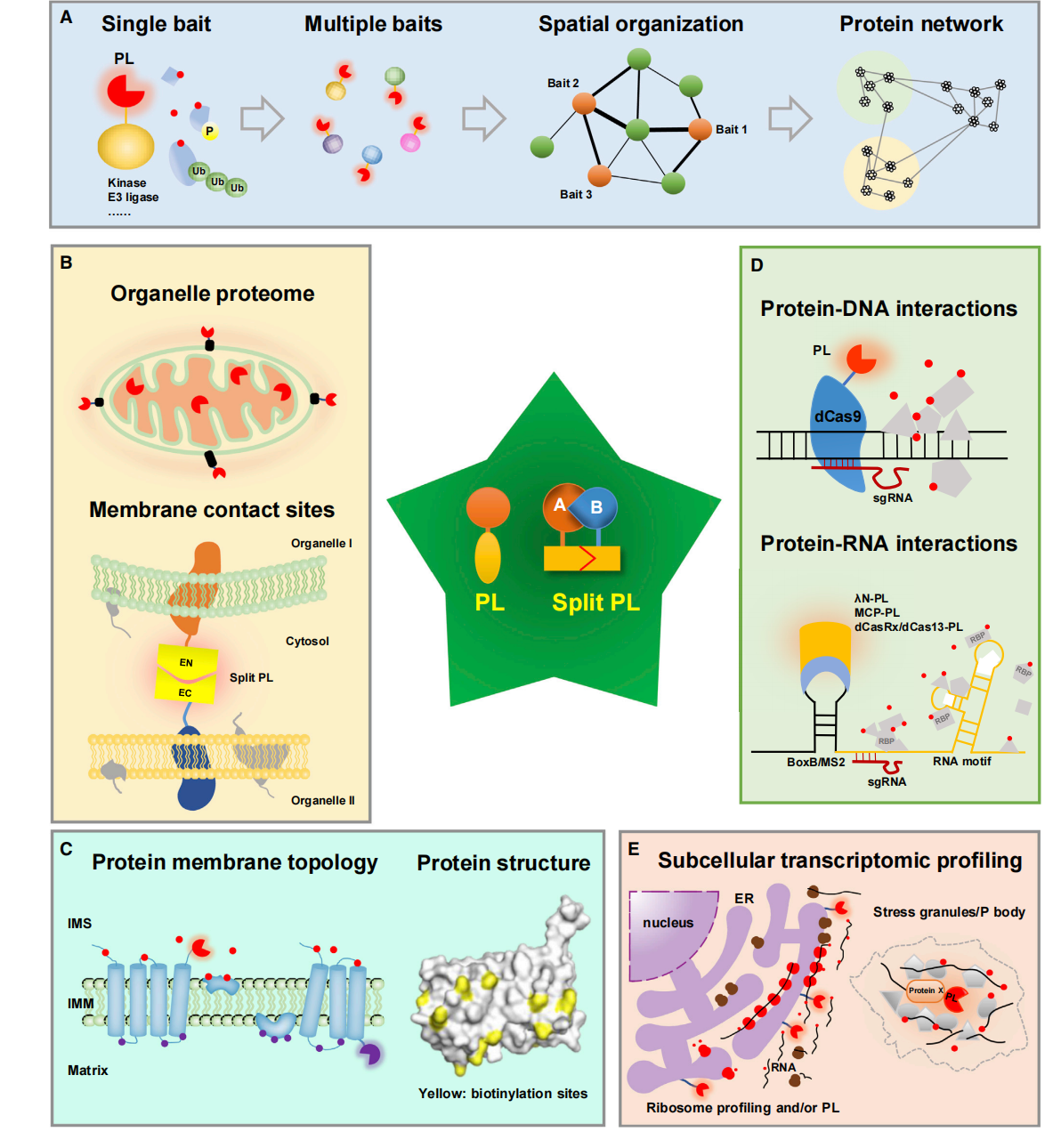

Application of proximity labeling technology

Protein-protein interaction (PPI) network analysis: Use PL to identify individual PPIs, decipher the spatial relationships between different proteins, and construct protein interaction networks.

Protein composition analysis of subcellular regions: used to analyze the protein composition of specific subcellular regions, such as mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum and cell nucleus.

Membrane contact sites (MCSs) research: This helps study the interactions between organelles, especially proteins at membrane contact sites. By using PL technology, proteins at these sites can be identified and studied, leading to a better understanding of intracellular communication and material transport.

Used to determine the topological structure of proteins: It can reveal the topological structure of membrane proteins and help understand their functional roles in signal transduction and molecular transport.

Analysis of protein-nucleic acid interactions: used to study DNA-protein and RNA-protein interactions, including the interaction of transcription factors with specific genomic sites.

(Data source: Yang X, et al. Plant Commun. 2020)

Discovery of new biomarkers or target proteins: Proximity labeling can be used to study the interactions between drugs and their target proteins and RNAs, which is crucial for drug development and target validation. This approach can identify the drug's direct target, as well as the signaling pathways and biological processes that the drug may affect.

Identification of E3 ubiquitin ligase substrates: Proximity labeling technology can be used to identify E3 ubiquitin ligase substrates, which is important for understanding how drugs regulate protein stability and function through the ubiquitin-protease system.

(Data source: Huang HT, et al. Nat Chem Biol. 2024.)

Important technical considerations for proximity labeling

1. Choosing the right proximity label: When selecting the best enzyme for a specific experiment, the characteristics of different enzymes need to be considered. For example, APEX and HRP require specific substrates and H2O2, which limits their use in animals. BioID and TurboID, on the other hand, are more suitable for in vivo use due to their higher catalytic activity and faster kinetics.

(Data source: Cho KF, et al. Nat Protoc. 2020)

2. It is crucial to experimentally verify that the fusion to the PL enzyme does not disrupt the native function and localization of the bait protein.

3. To generate bait-enzyme fusions, CRISPR knock-in of endogenous genomic loci or low-titer lentiviral delivery is preferred over transient trans infection to minimize artifacts due to bait overexpression.

4. The amount of input material (e.g., number of cells) and labeling time need to be carefully weighed against the size of the target proteome to ensure sufficient biotinylated material for MS detection with high depth of coverage.