Background

The increasing sophistication of machine learning algorithms has enabled the prediction of protein structure based solely on amino acid sequence, and these methods have highlighted that the native structure of most proteins represents an energy minimum determined solely by the interactions between the protein's amino acids. However, these methods are limited in their ability to predict native structures: we still cannot accurately predict the primary mechanisms used by a polypeptide to fold from its unfolded state to its native structure, and subtle changes in protein sequence can lead to drastically different folding mechanisms. Kinetically stable proteins may fold only once during their lifetime, so modulation of the codon-mediated precursor cycle of protein folding can have lasting effects. Protein synthesis is slower than many folding reactions and depends on the presence of synonymous codons in the protein-encoding sequence. Synonymous codon substitutions have the potential to modulate cotranslational protein folding mechanisms, and a growing number of proteins have been identified with folding mechanisms that are sensitive to codon usage.

On September 12, 2024, researchers published an article titled "The Effects of Codon Usage on Protein Structure and Folding" in Annual review of biophysics. The article synthesizes recent developments to describe the effects of codon usage on protein structure and folding mechanisms, including downstream effects on fitness, focusing on the effects of synonymous codon changes on functional protein production, especially co-translational protein folding, multimeric protein assembly, and membrane targeting and secretion.

The relationship between codons and protein folding

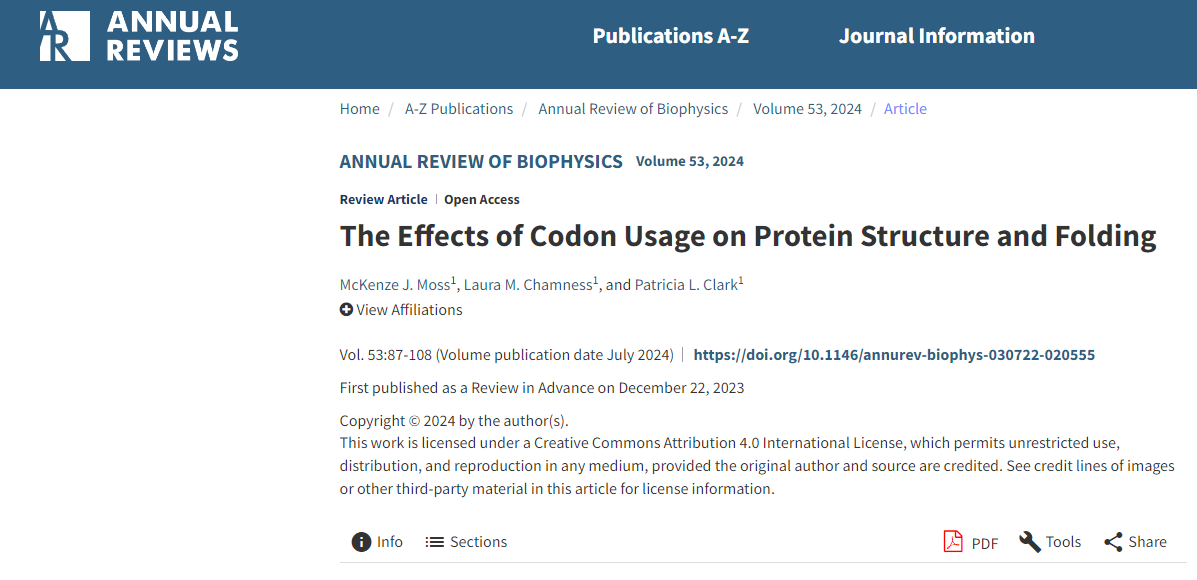

The classic Anfinsen experiment has now been used to attempt to refold thousands of different proteins , and it has been found that only a small fraction can be found to reversibly refold within a smooth, funnel-shaped energy landscape. Most proteins, especially those that are large, multimeric, or have complex structural topologies, tend to misfold and aggregate rather than refold correctly when diluted out of a denaturant.

A universal feature of protein folding in the cellular environment is that every protein in every cell can begin folding upon exiting the ribosome's exit tunnel. Co-translational folding, paced by the ribosome's elongation rate, represents a fundamentally different starting point than the refolding of full-length proteins upon denaturant dilution. A key factor regulating the elongation rate is synonymous codon usage. Synonymous codon substitutions, which do not alter the amino acid sequence, can alter the ribosome's elongation rate by more than 10-fold. Sequences encoding highly abundant proteins are enriched in subsets of synonymous codons, and these subsets are positively correlated with high cognate acceptor tRNA abundance, genome-wide abundance, and faster translation elongation.

Effects of codon optimization on water-soluble protein folding

As soon as a polypeptide chain exits the ribosome, even while it is still within the ribosome exit tunnel, stabilizing contacts can begin to form between amino acid residues in the N-terminal portion of the nascent polypeptide chain. Large, multimeric, or multidomain proteins are more susceptible to misfolding and aggregation than small, single-domain proteins with a low order of contacts. Wild-type messenger RNA transcripts typically contain both rare and common codons to enable efficient translation and functional protein production. Synonymous codon substitutions for more optimal (common) or non-optimal (rare) codons can alter protein folding pathways, leading to misfolding, aggregation, and/or degradation.

Co-translational folding of monomeric proteins

While codon optimization can increase gene expression, it can also affect the final protein structure due to alterations in cotranslational folding pathways. Introducing optimal codons does not always benefit protein function. For example, replacing the rare codon NNU in Neurospora crassa with the commonly used (in Neurospora) NNC codon increased mRNA and protein levels in the NNC mutant, suggesting that the WT NNU codon represses gene expression. However, introducing the NNC codon also altered CPC-1's stability and native structure, resulting in differences in its in vivo degradation rate and in vitro trypsin digestibility, and negatively impacting CPC-1 activity and Neurospora growth rate.

Assembly of multimeric proteins

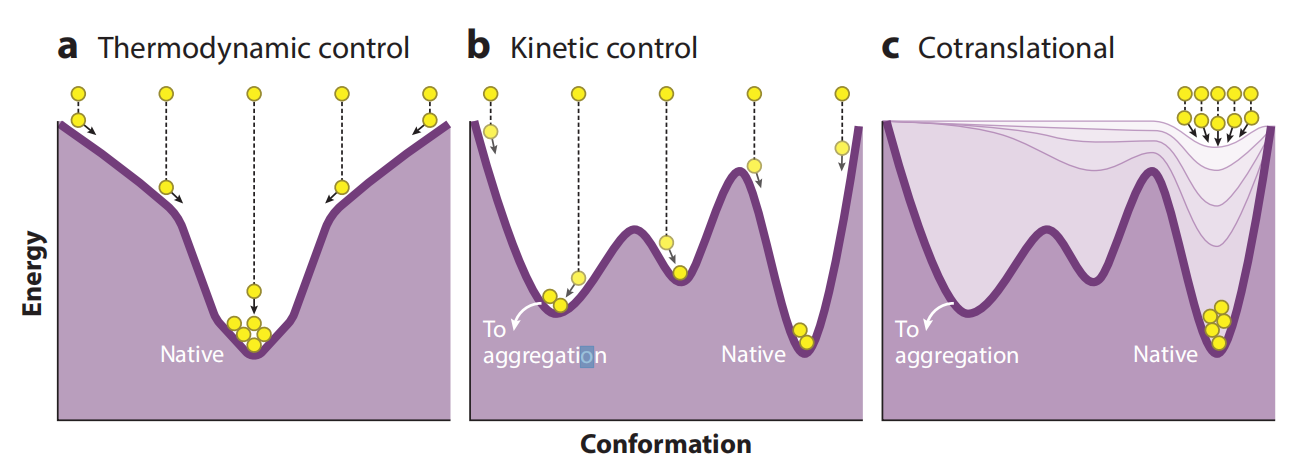

Compared to monomeric proteins, multimeric proteins must not only fold correctly but also assemble with other subunits. Depending on the native structural topology, assembly can occur before, during, and/or after the folding of individual polypeptide chains. Assembly that occurs before folding is complete can promote the formation of entangled native structures, where the native structure of each subunit depends critically on interactions with neighboring subunits. Assembly with other subunits too early or too late during the folding process can lead to deviations from the path of native multimeric protein assembly, including misassembled soluble states and aggregation.

Co-translational assembly coordinates the correct folding of multimeric proteins. By coupling co-translational protein folding with assembly, cells can increase folding yield and counteract the increased aggregation tendency of multimeric proteins. Multimeric proteins can be divided into two categories: homomers and heteromers. Four possible assembly mechanisms for multimeric proteins are possible: Co-co (cis), Co-co (trans), Co-post, and Post-post. In eukaryotes, Co-co (cis) is only compatible with homomeric protein assembly. Many multimeric proteins (primarily homodimers) assemble co-translationally via the Co-co mechanism (either in cis or trans).

The co-translational assembly of multimeric proteins depends on the affinity between partially synthesized polypeptide chains and the location of interacting segments along the nascent chain. Another key factor is the local concentration of interacting segments within the nascent polypeptide chain, which is influenced by elongation rates and ribosome density. Synonymous codon changes can affect the final structure and function of multimeric proteins , suggesting that synonymous codons may influence assembly by modulating folding pathways.

Effects of codon usage on secretion and transmembrane protein folding

Proteins of the secretory pathway have complex folding pathways, many of which are transported co-translationally and can initiate co-translational folding, and both folding and secretion can be influenced by synonymous codon usage. Successful targeting and folding of secretory proteins has important implications for cellular fitness.

Membrane targeting and intracellular trafficking

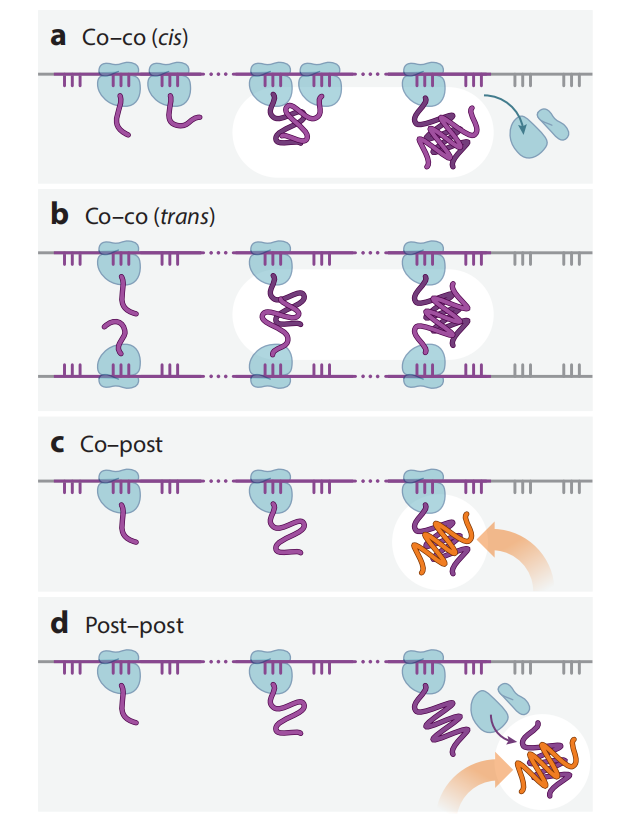

In eukaryotes, proteins in the secretory pathway are co-translationally targeted to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane by signal recognition particles (SPRs). SRP binding promotes correct translocation, folding, and trafficking within the cell by coordinating translation elongation and targeting of nascent ribosome chains (RNCs) to the translocon. Synonymous codons can alter SRP-mediated targeting of secretory and membrane proteins to the ER membrane by regulating ribosome elongation rates during a critical early window of protein synthesis and SRP binding.

Many transcripts encoding membrane and secretory proteins are enriched for nonoptimal codons approximately 40 codons after the SRP binding site . Nonoptimal codons at this position can slow elongation. These slow-translating codons may be the cause of elongation stalling, thereby targeting the RNC-SRP complex to the membrane's Sec61 transporter. Upon binding to the SRP receptor, elongation resumes, accompanied by translocation by Sec61. Water-soluble proteins are translocated into the ER lumen through the Sec61 pore, while integral membrane proteins are translocated into the phospholipid bilayer via Sec61 and other insertion mechanisms. Rapid elongation at optimal codons suggests that the signal sequence may bypass SRP binding. Without SRP binding, elongation is not paused, and RNCs are unable to properly associate with transporters on the ER membrane.

Synonymous codons have also been shown to affect membrane targeting and cellular trafficking through SRP-independent pathways. Kesv is a viral protein that has a structure similar to a eukaryotic potassium channel; when expressed in eukaryotic cells, it is usually targeted to mitochondria but can be translocated to the endoplasmic reticulum through synonymous substitutions.

Integral membrane protein folding

In addition to N-terminal elongation stalling due to SRP binding, ribosome pausing due to slow translation codons has also been observed in membrane proteins that are co-translationally integrated into the membrane, approximately 70 codons after the subsequent transmembrane α-helix. Although the mechanism is unclear, the spacing between the transmembrane α-helix and the suboptimal codon suggests that when translation is predicted to slow, the helix will exit the exit channel. Therefore, ribosome pausing may promote the binding of the transmembrane domain to the bilayer and/or the membrane insertion machinery.

The cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator ( CFTR ) belongs to the ABC transporter class of integral membrane proteins. Synonymous codon usage has been shown to affect CFTR translation, folding, and function. Proper folding of the β-sheet core of the first nucleotide-binding domain 1 (NBD1) of CFTR depends on local elongation. Elongation in the WT sequence delays the positioning of β-chain S6 until the two subsequent β-chains emerge from the ribosomal exit tunnel, allowing coordination of native contacts between the β-chains and the upstream α subdomain. Synonymous mutations in commonly used codons in this region lead to β-chain misfolding, resulting in aggregation . Synonymous mutations can also synergize with nonsynonymous mutations to alter CFTR folding. A synonymous mutation at Thr854, changing from ACT to ACG, can affect co-translational folding when present in conjunction with other mutations.

The impact of codons on genome evolution

Like all parts of the genome, protein-coding sequences accumulate mutations over time, which are subject to selective pressure to optimize fitness. Therefore, synonymous mutations may be subject to natural selection. Selective pressure to maintain efficient co-translational folding may lead to conserved codon usage patterns.

Unresolved issues

Despite significant progress, several significant obstacles remain preventing us from gaining a clear understanding of the specific changes that occur in co-translational protein folding pathways when elongation rates are altered.

1.The lack of an experimental method that can selectively report subtle structural changes in nascent chain folding intermediates on the rapid timescale of protein synthesis has hindered our further understanding of the effects of codon substitutions on protein folding.

2.The lack of a model to accurately and quantitatively predict elongation rates for any messenger RNA sequence of interest has led to reliance on imperfect proxies, such as equating rare codons and/or low transfer RNA gene copy number with slow elongation rates.

3.Synonymous codon substitutions can affect many aspects of co-translational folding upstream of functional protein production. Disentangling folding-specific effects from those affecting other aspects of protein production can be challenging, particularly because such effects can be subtle and/or cumulative. Historically, most genome-wide association studies have overlooked synonymous substitutions associated with disease, hindering our understanding of the contribution of synonymous variants to disease.

Summarize

For many proteins, the rate of folding is determined by the rate of translation elongation, and synonymous codon substitutions can alter elongation rates by as much as 10-fold without constraining the encoded amino acid sequence. Using synonymous codons can lead to excessively rapid translation, resulting in misfolding or aggregation, affecting protein structure and function. Synonymous codon substitutions can act synergistically with nonsynonymous substitutions to amplify or mitigate the effects on protein folding. However, few experimental methods exist to quantify translation elongation rates and co-translational folding mechanisms in cells, posing a challenge to developing a predictive understanding of how biology optimizes codon usage to regulate protein folding.